M I C H I

道

L A V O I E

2016 - 2021

Durant le mois de juillet 2016, le collectif Neotravelmakers a suivi le tracé historique de la route du Tokaido au Japon, à pied et en train, durant trois semaines. Ce jeu de piste territorial avait pour but de déceler les traces visibles dans le paysage contemporain des 56 étapes de la route représentées par Hiroshige, éminent peintre japonais de la première moitié du 19ème siècle.

Le Tōkaidō, la route de la mer de l’Est, est l’une des cinq routes majeures du Japon. Elle puise ses racines à l’époque Heian (794 - 1195) et elle constitue toujours aujourd’hui l’axe principal qui relie Tokyo à Kyoto. Renommée “route nationale n°1”, le Tōkaidō est resté le coeur historique du développement de l’archipel. L’urbain a changé, s’est densifié, les axes de communication se sont démultipliés, les autoroutes et voies de chemin de fer rapides se sont développées en suivant à quelques exceptions près l’axe de la route originelle.

Au regard des transformations profondes de la région dans laquelle s’ancre la route originelle, les éléments encore visibles du chemin dans le territoire actuel sont essentiellement d’ordre toponymiques, géographiques, topographiques et architecturaux.

Le Tokaido d’hier serpentait dans un paysage naturel, où l’anthropisation ne s’étendait qu’aux zones agricoles, aux villages d’étapes et à la route elle-même. Parcourir le Tokaido aujourd’hui, c’est s’enfoncer au coeur d’un territoire presque totalement urbanisé et très maîtrisé, innervé par un énorme réseau d’infrastructures.

Indéniablement, le collectif Neotravelmakers a du adapter son regard, durant son périple, et sortir de son statut de touriste occidental pour tenter de s’imprégner du territoire japonais et des notions de spatialité qui lui sont propres, afin de retrouver des indices de localisation des lieux dépeints par “le paysagiste”, dans l’optique de rester fidèle à la localisation originelle des stations. Comme auraient pû le laisser supposer les Ukiyoe d’Hiroshige, les lieux traversés étaient rarement des lieux de repos, de contemplation, mais plutôt des lieux de transit et de passage.

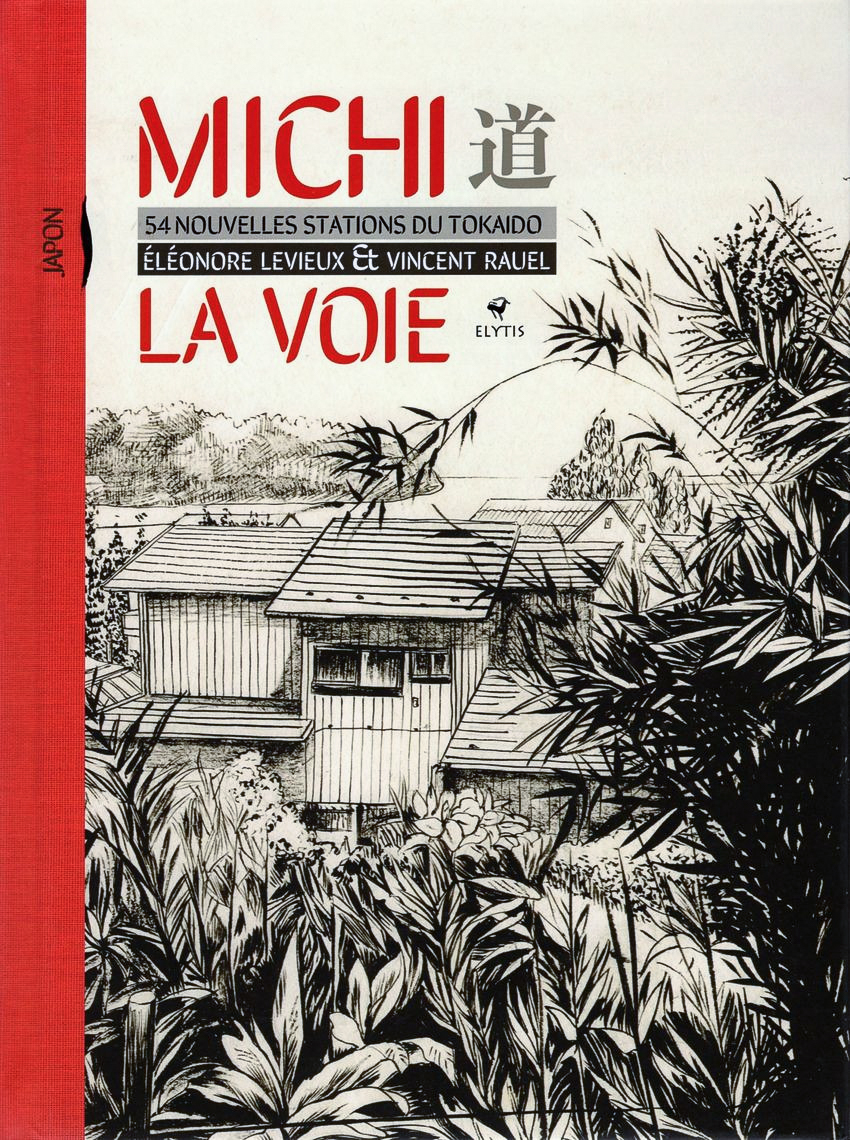

Ce projet a donné lieu à la publication du livre éponyme MICHI, aux Éditions Elytis, en 2021.

︎ CLIQUEZ SUR LES IMAGES POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN :

TEASER ︎︎︎

︎ MICHI, LE LIVRE

Cliquez sur les images pour plus d’informations.

During the month of July 2016, the Neotravelmakers collective followed the historic Tokaido road in Japan, on foot and by train, for three weeks. The goal of this territorial treasure hunt was to identify the visible traces in the contemporary landscape of the 56 stages of the road represented by Hiroshige, an eminent Japanese painter, during the first half of the 19th century.

The Tōkaidō, the East Sea Route, is one of Japan's five major highways. It has its roots in the Heian period (794 - 1195) and is still today the main axis connecting Tokyo to Kyoto. Renamed "National Highway No. 1", the Tōkaidō has remained the historic heart of the archipelago's development. Urban life has changed, has become denser, communication axes have multiplied, highways and high-speed railways have developed, following with a few exceptions the axis of the original road.

In view of the profound transformations of the region in which the original route is anchored, the elements still visible of the road in the current territory are mainly toponymic, geographical, topographical and architectural.

Yesterday's Tokaido meandered through a natural landscape, where anthropization extended only to agricultural areas, stopover villages and the road itself. To explore the Tokaido today is to go deep into the heart of an almost totally urbanized and highly controlled territory, innervated by an enormous network of infrastructures.

Undeniably, it was necessary to adapt the gaze, during the journey, and to get out of the status as Western tourists to try to imbibe the Japanese territory and the notions of spatiality that are specific to it, in order to find clues of the location of the places depicted. by “the landscaper”, with a view to remaining faithful to the original location of the stations. As the Ukiyoe of Hiroshige might have suggested, the places crossed were rarely places of rest, contemplation, but rather places of transit and passage.

︎ Prev Next ︎